The degree to which kitchen and cooking facilities are allowed in HMOs can often cause considerable confusion among developers. This can arise mainly due to overlap between Planning and Housing licensing regimes.

As a result, it is not unusual for developers to inadvertently find they are under investigation from the Council’s Planning Enforcement Team for converting a property into flats that do not meet with national space standards.

In this article, we look back on a recent case with one of our clients, how the problem arose, and how this was resolved.

‘Self-contained’ HMO rooms

The heading above is a little tongue-in-cheek. You cannot have an HMO room which is self-contained (i.e. bed, cooking facilities, bathroom and WC). This would be a flat in Use Class C3. An HMO would be in Use Class C4 or, if there are more than 6 bedspaces in the property, within Sui Generis (a miscellaneous category outside the other use classes).

Our client sought to maximise the occupancy in his house, with the benefit of extensions to the property. These extensions were carried out lawfully under permitted development long before we were involved, many years ago, whilst the property was still in use as a single dwelling house.

However, instead of seeking the advice of a planning consultant before sub-dividing the property, he asked his builder. I don’t know many planning consultants who feel confident about advising a client how to construct a wall or lay services through a building, yet I often find non-planners giving advice on planning policy, strategy or law! The builder had sought advice from the Housing licensing team on the proposed layout of 9no separate rooms, each with their own kitchen and hobs, and bathrooms and WCs. The licensing team looked at the plans with regard to the application of the Housing Acts, not in terms of planning legislation. They confirmed that the plans were acceptable and the builder proceeded with the works.

The works were done to a good standard, but this only complied with Housing Act standards. These standards do not just cover rooms that share facilities, such as a bathroom or kitchen/dining room, but also cover houses converted into self-contained flats (Housing Act 2004, section 254(1)). Therefore, when the housing officers were asked the question, they were able to answer it because the property comprised a form of HMO that is covered by the Housing Acts – i.e. a building comprising self-contained flats (section 245(3)). However, this conflicts with Planning Law, which regards self-contained flats as being in a different use class to HMOs.

‘Curtain twitchers’

In many instances, developers can get away with internal changes of use to a building, as these often lay undetectable for many years. The usual trigger to a visit from a Planning Enforcement officer will be from a neighbour who spots a change to the exterior of the property, such as a new outbuilding, roof lights or dormer windows, that do not have planning approval or benefit from a lawful development certificate. We sometimes refer to these complainants as ‘curtain twitchers’.

Our client had in this case erected a large outbuilding without consent, which invited complaints from immediate neighbours. The irony was that many of these people had their own equally-large outbuildings (one or two of which we suspected were being used as ‘beds in sheds’ at the bottom of their gardens).

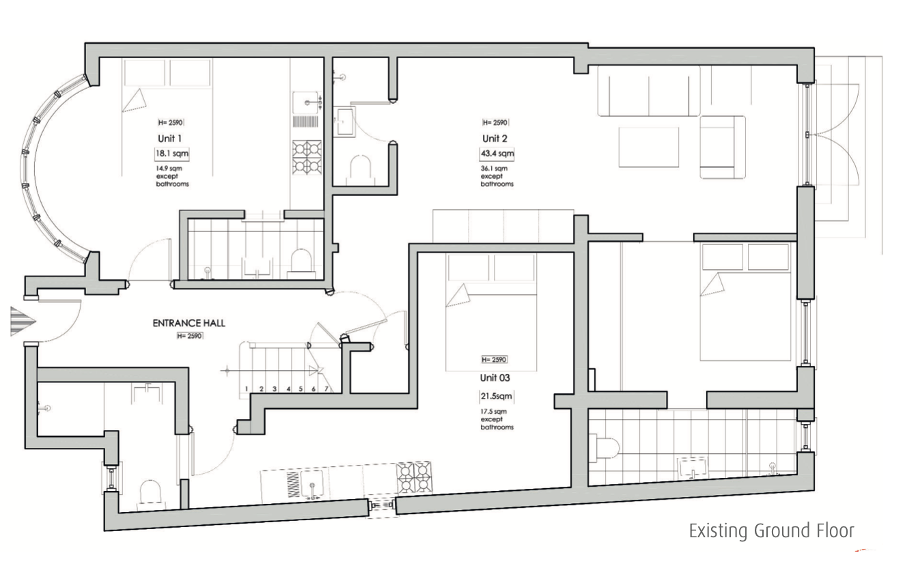

Having received these complaints, the enforcement officer had to undertake an inspection not just to the garden and outbuilding, but also to the rest of the property, in case he could conclude that the outbuilding benefitted from permitted development if the house was in use as a single dwelling house. This is when the unlawful nature of the existing HMO use was discovered.

Lawful Development Certificate

There was a borderline case to try to preserve the existing 9no units. Our initial advice to the client and advice from a Planning QC had highlighted inconsistencies in the client’s evidence, but the costs of having to convert the property back and the loss of rental income in the meantime meant that, to the client, this was a risk worth taking.

For HMOs, they need to be proven to have been in continued lawful use for at least 10 years (the 4-year rule for immunity applies only to single family dwelling houses and flats in Use Class C3); First Secretary of State v Arun District Council & Another [2006]. However, in this case, as the 9no units were all self-contained, the relevant period was 4 years.

The evidence struggled to reconcile various inconsistencies in the planning history, such as when the property was first rented out and occupied outside Use Class C3 when lawful development certificates were being sought or granted for extensions to the property on the assumption that it was at the time in use as a single-family dwelling house. Officers mooted that the previous consents and permission for these extensions might not be valid and that these consents might have been obtained under false or misleading declarations at the time as to their use. Never a good start to a case!

The Council also raised concerns regarding breaks in occupation in the 4-year period for each and every flat. Evidence must show that each flat was occupied for a continuous period of 4 years; subject to allowable minor breaks (e.g. 2-4 months) to allow for re-letting or minor refurbishment and marketing.

Some of the tenancies did not start until after parts of the extensions to the property had been completed and this also weakened the case, with this further compounded by the poor hand-written records and lack of properly signed and dated tenancy records.

Councils will also look at bank records to try to verify that rental income was being received over the relevant time for the rooms or flats concerned. These records can be redacted to protect client privacy, and some Councils will not post this evidence online in any event for DPA reasons, but will still take the information to account. If such records are to be provided, then the evidence must clearly explain what they show and in respect of which flat or room.

Keeping Planning Enforcement Officers informed

Throughout the time taken to collect and present this evidence and make this application, it should be remembered that a Planning Enforcement case is running.

Every month, at the end of every Planning Committee meeting, there is a part of the meeting where officers update Councillors on the progress being made on enforcement investigations. Councillors might also contact officers in any event to put pressure on them to take action or resolve the situation, if neighbours are complaining to their ward councillors.

Therefore, it is important to ensure that Planning Enforcement Officers are kept in the loop throughout any attempts to resolve planning cases through planning or lawful use applications to their colleagues elsewhere in Development Control teams.

By keeping these officers in the loop throughout you gain their confidence that positive action is being taken to try to resolve the situation, which could help to avoid an escalation to more formal notices or even court action. Also, officers across the Planning Department will generally tend to be more willing to work with the developer to achieve an outcome that hopefully works for everyone.

Conversion to 3no Flats (Full Planning)

This was now the only route left to my client as the Council would not allow planning permission for 9no self-contained flats that are all below national and London Plan space standards, and we would not prove that the use of the property for 9 flats was now lawful after 4 years.

In the London Borough of Barnet, where this property was located, there are no particular thresholds on the conversion of single-family dwelling houses into flats. Instead, the principle of change of use is largely focussed on the character of the area. Therefore, before assessing the quality of the flats themselves or the impacts on neighbours or local highways conditions, I recommend the following:

- Check if the Council has a threshold for conversions in a street (e.g. in percentage terms or a particular number) or any type of ‘conversion stress’ policy.

- Conduct a survey of the apparent use of the residential properties in a street as single houses, flats or HMOs (e.g. regard to bins, door buzzers, separate street doors with its own numbering, Council licensing records, online Planning records).

- Compare the total number of occupants proposed with the number of bedspaces in the existing lawful house.

The application also had to include the retention of the garden outbuilding, which of course had triggered the need for these applications in the first place.

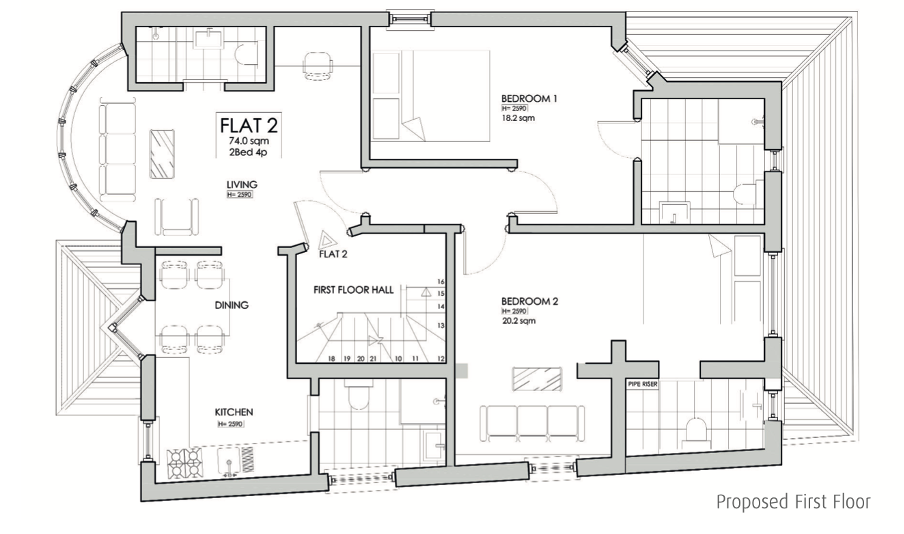

Minor alterations to internal layout were negotiated with the officers, so as to try to retain the least amount of disruption to the existing services and pipes through the building, and also to ensure where necessary obscured glazing to some windows in order to address possible privacy concerns.

The application went to Committee and permission was granted for the conversion of the property to 3no flats:

Threat of Planning Committee Bias

During the Planning Committee hearing, one of the Councillors present had written in to the Department before objecting to the application! The Councillor should not have been on the Committee and I think a stronger body of officers and more robust Chairman would have put more pressure on the Councillor concerned to step down from the Committee for our item. She did not even declare a prior interest in the matter at the start of proceedings!

It is up to a Councillor whether or not they feel they should step down or step-aside, but I firmly believe that the law should be changed to prevent Councillors from sitting to hear a matter if they have already expressed a clear opinion against a scheme. How can they be trusted to either keep an open mind about it or to not say anything that might contaminate the rest of the Committee?! After all, “Justice must not only be done, but it should be seen to be done”.

We raised the issue with the Planning and Legal Officers in advance of the hearing. However, it is often best not to raise this during the public meeting and focus a personal attack on a member of the Committee, but instead to stress the positives in the application during the speech.

Conclusions

Confusion and misunderstanding between similar but different regimes in property development – such as Planning and Housing – can often lead to possibly expensive mistakes in execution.

Whenever seeking to intensify the use of a property or change its use, then expert planning advice should be sought as soon as possible in order to understand the implications and form a practicable and viable strategy.