Converting Pubs to Residential Use

Introduction

Last orders for the business!

Alternative Provision & Competition

The premises operated in a very competitive environment. There were 13 other licensed public houses operating within a 1 mile radius of the premises; the radius we looked at was specifically dictated in this case by the Council’s local plan policy.

This was clearly borne out by the pub’s business accounts. We went back 5 years, and the profit and loss account showed a slow and steady decline in the business. Sales went from £87,000 in 2017 down to £18,726 in 2021 – a drop of over three quarters of the 2017 revenue. Although much of this was down to the impact of COVID in the 5thyear, it was already falling on an annual basis.

This was clearly not down to the management of the business. The present owner of the business was very experienced and had strong local connections. It is very unlikely that it would somehow completely turnaround as a business and start turning a significant profit again if a new owner with new ideas was ‘parachuted’ into the business overnight.

Marketing and other factors

The premises were also actively marketed in the local press and on Rightmove for a total in excess of 12 months. There was very little interest in taking the premises on. In addition, in terms of alternative uses for the pub that might serve the local community in some way, instead of converting straight to residential use, we considered the following (all under Use Class E):

- Shops

- Financial and professional services

- Restaurants & Cafes

- Medical health Services

- Creches or day car nurseries

There was enough provision locally for all of these alternatives and thus little demand from potential occupiers for such uses.

In addition, it was important for us to remind the Council of the ‘human factor’ involved in this case. The business was not generating sufficient money for the publican and his wife to pay themselves a reasonable living wage, despite having operated the business for many years and consistently working around 10 hours per day. They had little to no quality of life and no viable exit from the business with having to use up their own savings, such as they were, to continue to run a dying business. This puts enormous physical, mental and emotional stress on people over time.

Conversion to HMO use

Firstly, the ground floor courtyard area needed to find a balance between space for bins and bicycle storage on the one hand,and on the other sufficient privacy for users of individual bedrooms and living rooms where the windows to some of these spaces were located close to entrances and storage which would be used by all occupants.

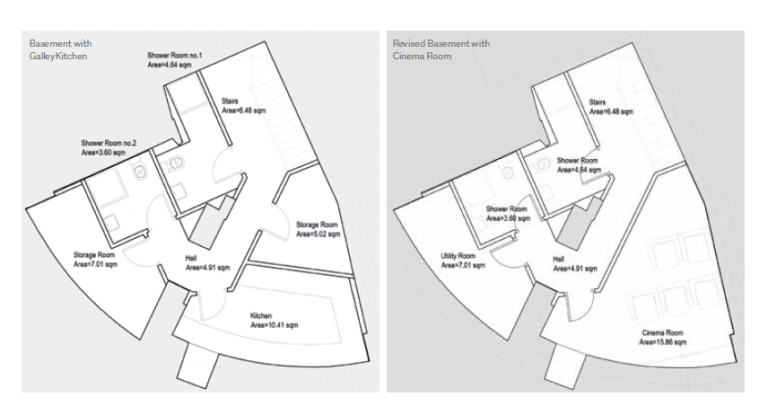

Secondly, the basement was a large, potentially underutilized space, unserved by any direct natural light and with the possibility of non-habitable, communal use.

Thirdly, the size and shape of the proposed living rooms to the HMO communal spaces, working around bedroom walls, stairwells and the overall ground floor internal plan created challenges in terms of configuration, circulation and adequate privacy and outlook from these spaces, linked with the first issue above.

Officers generally sought to push back on this proposed approach, as they were generally not supportive of the proposed layouts. Applying obscured glazing to habitable rooms can be a ‘Catch 22’, as it will assist with privacy, stopping passers-by and other residents from looking in, but will diminish outlook and possibly give rise to a sense of enclosure.

There can, though, often be a case for slightly more flexibility to be applied on standards of privacy vis-à-vis outlook in these situations. HMOs tend to be occupied by people who stay for a shorter time period (compared to self-contained apartments) and, as long as the living room has good quality space and outlook, some planning officers will not kick up too much of a fuss over the use of obscured glazing to bedrooms.

The use of the basement

The above image was sent through to the planners to convey the sense of what was proposed in terms of a kitchen in the basement. This kitchen would have freed up space on the ground floor for possibly one or two extra HMO bedrooms, adding possible rental and capital value to the scheme.

However, officers resisted this proposal, fearing that the space would be used for habitable purposes and thus, in the absence of natural light and ventilation and outlook, would be inappropriate for this use.

Such galley kitchen arrangements in basements are common with many HMOs but can often depend on the flexibility of officers and their discretion in how they apply planning policy, which can often be worded in a way that it is open to interpretation and not overly-prescriptive. Kitchens normally have to meet certain ventilation and other saftey requirements, but even in basements this can be accommodated, such as with the use of mechanical ventilation. A galley kitchen would also have prevented habitable use as there was no space in the design for a living or dining room – this would have had to be located at ground floor level. The layout would have been secured, and ultimately enforced, through a planning condition. That being said, kitchens are defined in the relevant local plan as ‘habitable rooms’ and also the BRE Sunlight and Daylight technical guidance normally seeks an adequate degree of natural light to kitchens and not a reliance on artificial lighting, hence this Council’s officers were particularly resistant to these proposals where other officers in different parts of the country might not have been.

This was the ultimate sticking point to this proposal and officers would not move on this.

Conversion to flats

It was decided ultimately to accept the refusal of the HMO proposals. We submitted an appeal to the Planning Inspectorate on the 2nd October 2022. The ‘Start Letter’ was received on the 31st March 2023 – 6 months later. We are still waiting on PINS’ decision, 11 months after the submission of the appeal.

Therefore, it was thought prudent in September 2022, when we became aware of the risk of refusal of the HMO scheme, to prepare a scheme for flats instead, but which substituted the galley basement kitchen for a ‘cinema room’ instead for one of the flats.

Conclusion

The principle of the change of use and case for it with pubs has to be very carefully and thoroughly researched from the outset. Every Council tends to take a unique policy approach to this matter, and this can sometimes cross-over with other factors such as impact on the local conservation area.

However, it also worth considering a primary and a secondary development strategy in these cases as there may be particularly contentious aspects of the proposed layout (e.g. a basement kitchen) that may need to be changed and a back-up plan pursued. Acute delays with PINS and the general unpredictability of the appeal process mean that it is best if you can ‘bag’ a viable scheme in the meantime if timescale and opportunity permits.